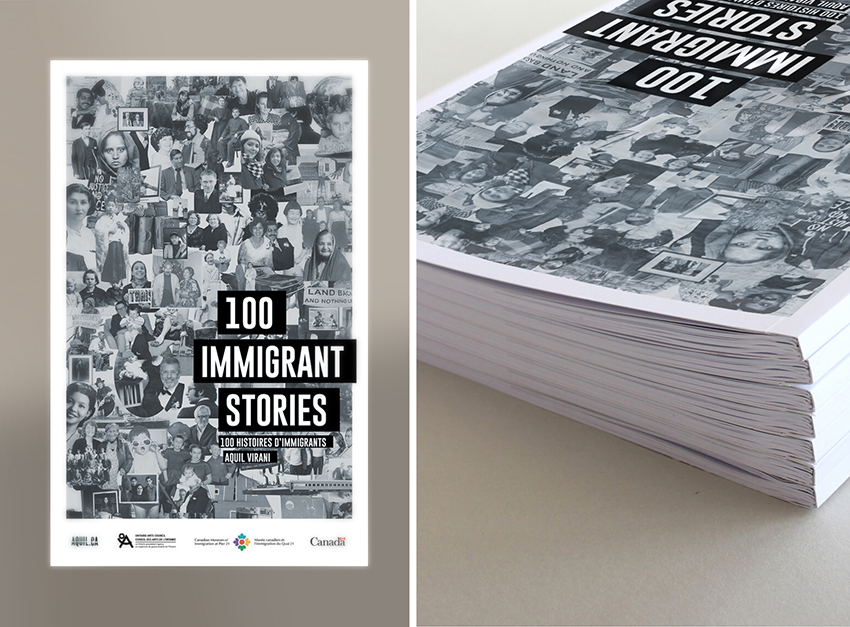

CelebrateHer: Installation

Welcome to CelebrateHer.

Cliquez ici pour la version française : CélébronsLa.

——————

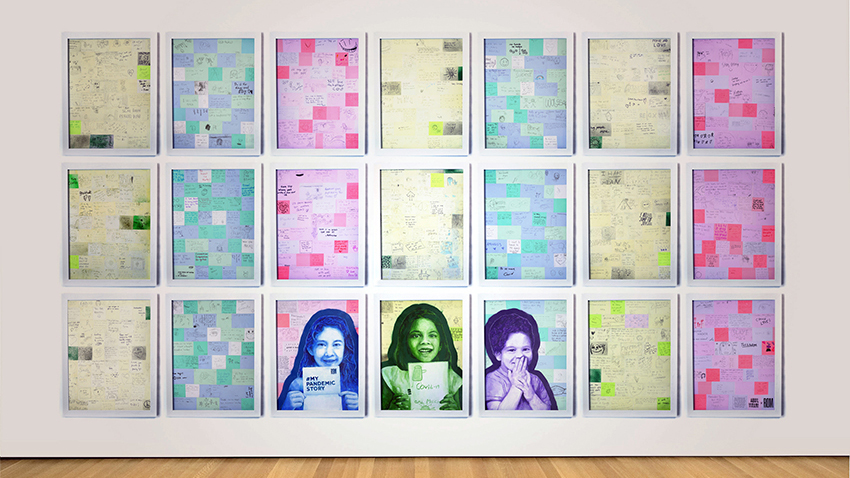

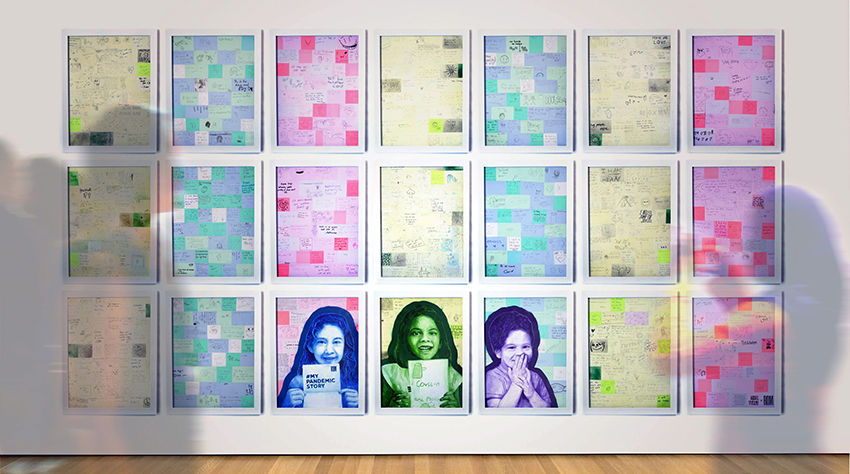

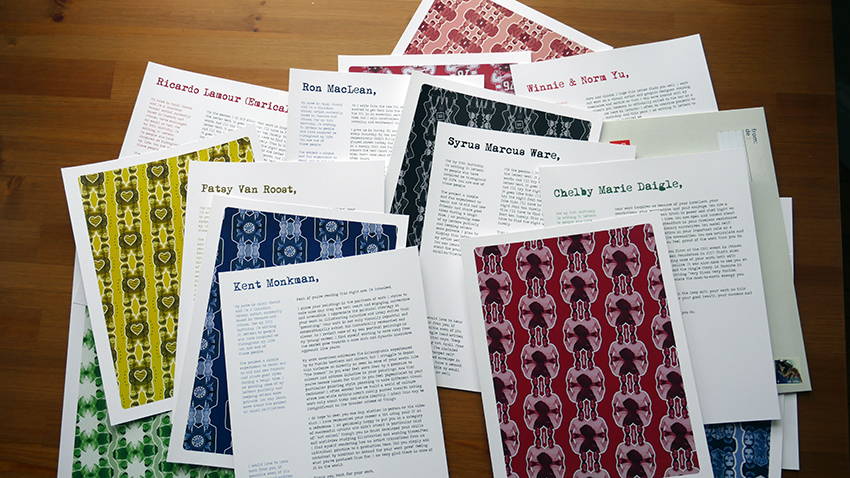

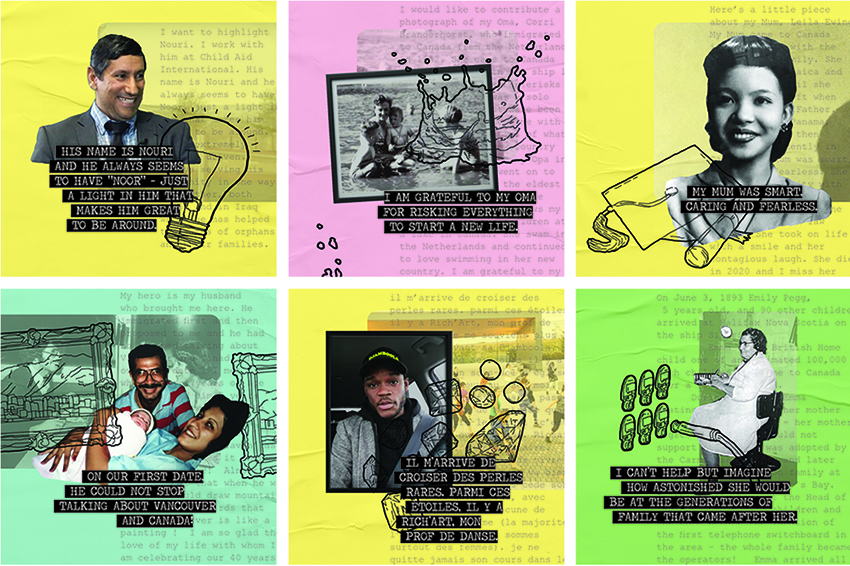

12 publicly-nominated women. 12 large-scale portraits. 12 rich, ongoing stories.

12 inspiring, everyday women are recognized in an ambitious feminist art collaboration, combining portrait paintings and micro-documentaries from artist Aquil Virani with a verbatim sound play crafted by writer Erin Lindsay and directed by Imago Theatre’s Micheline Chevrier.

——————

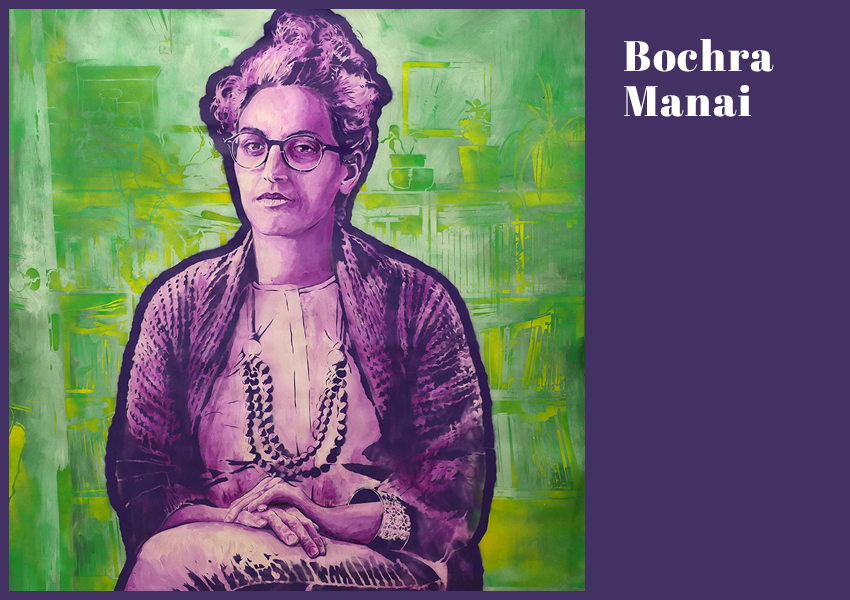

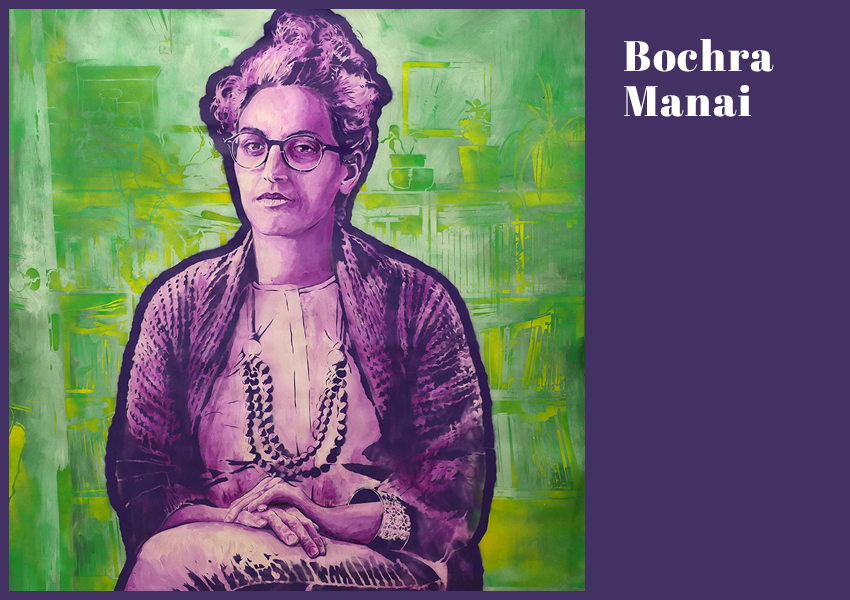

Bochra is a super smart lady with an incredible story. Alia’s nomination describes her, among other things, as an “one of the brightest spirits she’s ever met.”

She gives you her full attention. She is a researcher, a professor and an engaged citizen with a PhD in Urban Studies from the INRS-UCS. She’s a Muslim woman who chooses not to wear the hijab. She fled from political turmoil in Tunisia and eventually ended up in Montreal via France about ten years ago. The backdrop of her home office – with all of its book-filled shelves and messy, planted greenery – visually represents her academic passion fused with her domestic commitments as a young mother. The only book in the background that is legible among the spray-painted texture is “Aime comme Montréal.”

——————

——————

Naomi tells it how it is. She’s an Inuit woman, a mother, a daughter, a seamstress, and, as her nominator Anna Bunce puts it, “a spoke in the wheel, connecting people and communities together.”

She works in community health outreach for the Department of Public Health in Nunavut. I had hoped I would be lucky enough to meet Naomi in person while she was visiting Ottawa to accompany her father on a health-related trip, but fortunately, they found what they needed locally. Chatting over the phone with a 3-second time delay proved to be a wonderful exercise in patience and trust. In our conversation, Naomi was very giving of her time and her experiences. On social media, one of Naomi’s latest posts reads, “Takualugilli niruaqtaulautunga, one of the 12 nominated and selected. It’s finally sinking in.”

——————

——————

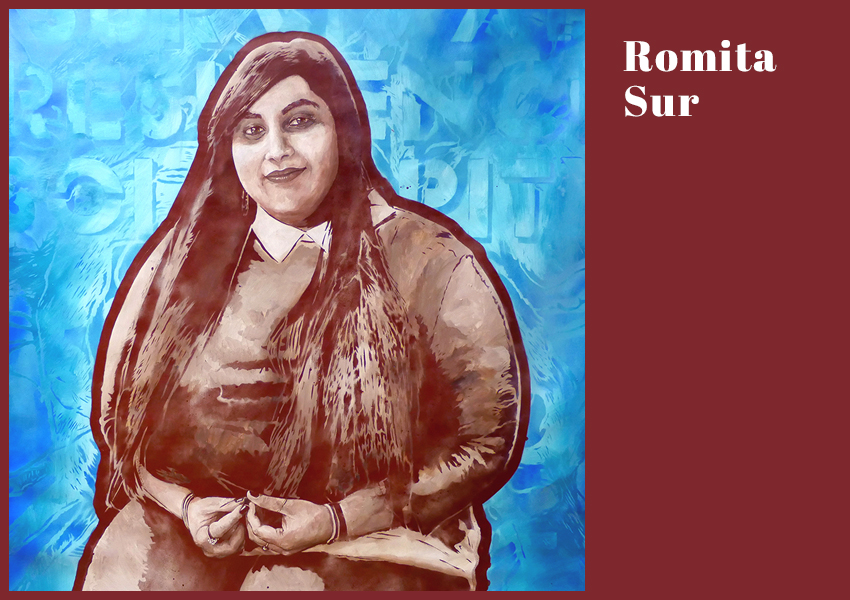

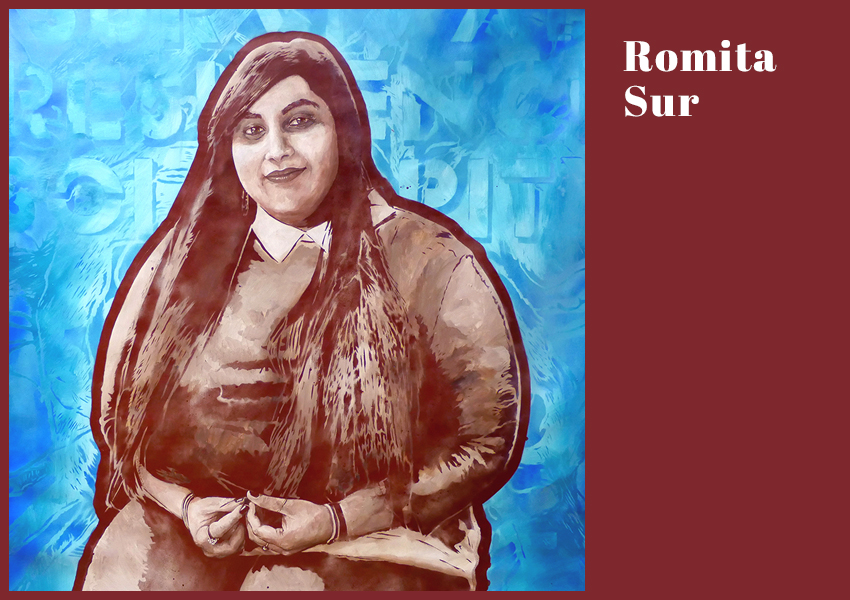

Romita is a badass woman of colour. She just recently graduated with her transsystemic law degree

– in both civil and common law – at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec.

When I visited Rom’s apartment, I was reminded of my hospitable Indian “aunties” who would offer me everything they had without hesitation. Unconditional kindness and love, personified. “We have water, juice, milk, some leftover iced tea. I just made some food, do you want some?” Romita is especially proud of her work with the Contours journal that promotes the voices of women in law. She co-founded the Women of Colour Collective that built a community around racialized women in her faculty. A banner that the WOCC commissioned features the words, “Survival, Resilience, Solidarity,” so I got in touch with the talented Oakville-based illustrator Izabela (Izzy) Stanic to see if I could remix her artwork into the painting. Izzy was delighted. (Check out izzystanic.com.)

——————

——————

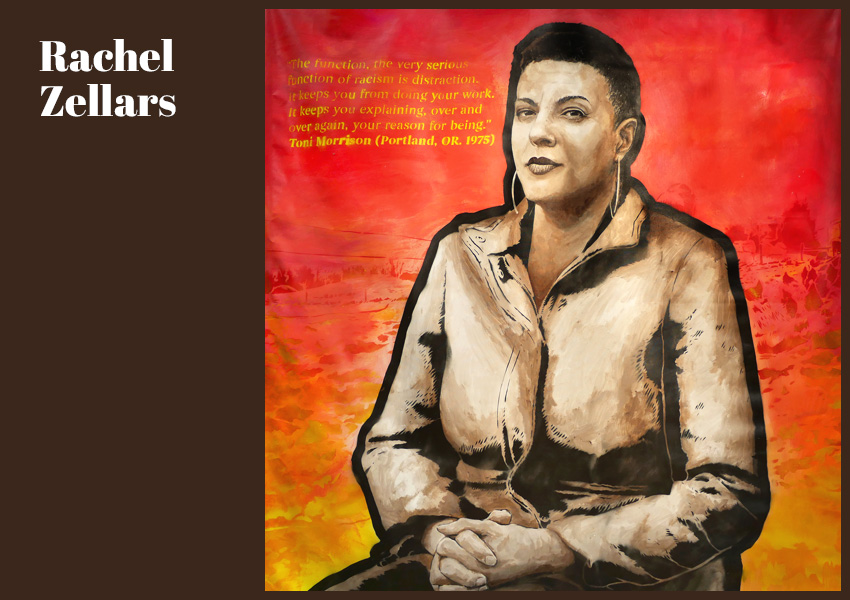

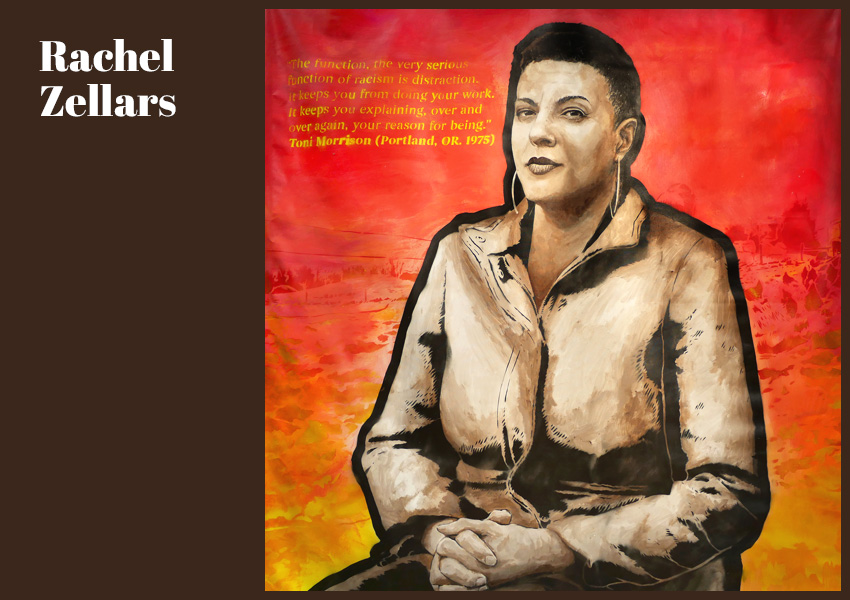

Rachel talks and you listen. She’s a single mother, a researcher and educator, and an anti-violence activist.

I find her command of language mesmerizing. She holds a PhD in the Department of Integrated Studies within the Faculty of Education at McGill University. I first met Rachel in passing during organizational meetings of the first Manif des femmes (Women’s March) back in January 2017 when she was serving as the Executive Director of Girls Action Foundation. In addition to her intellect, the humanity and warmth in her leadership style made you feel like, “I want to be on her team.” And yet, perhaps unexpectedly, Rachel is a farm girl. Her favourite quote pays tribute to her scholarly pursuits, floating among the earthy backdrop of farmland in Moravia, New York.

——————

——————

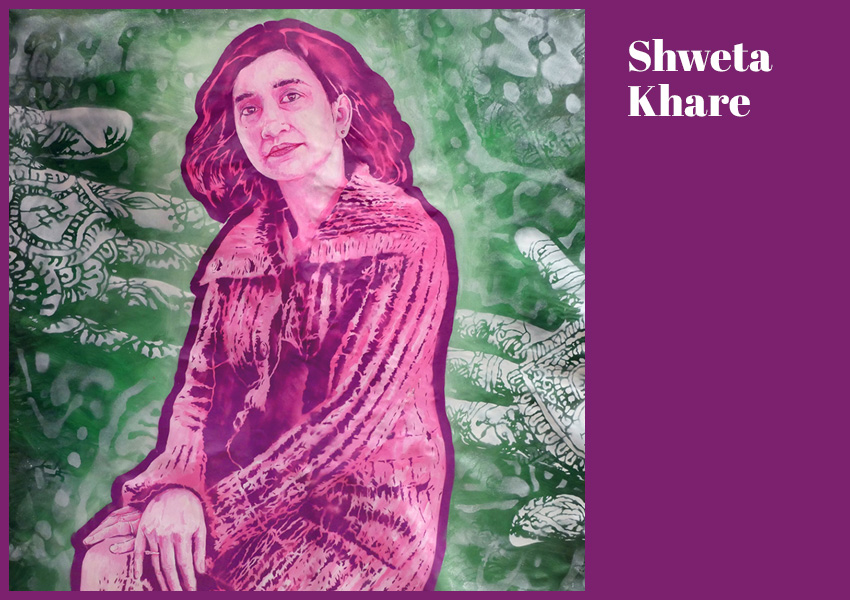

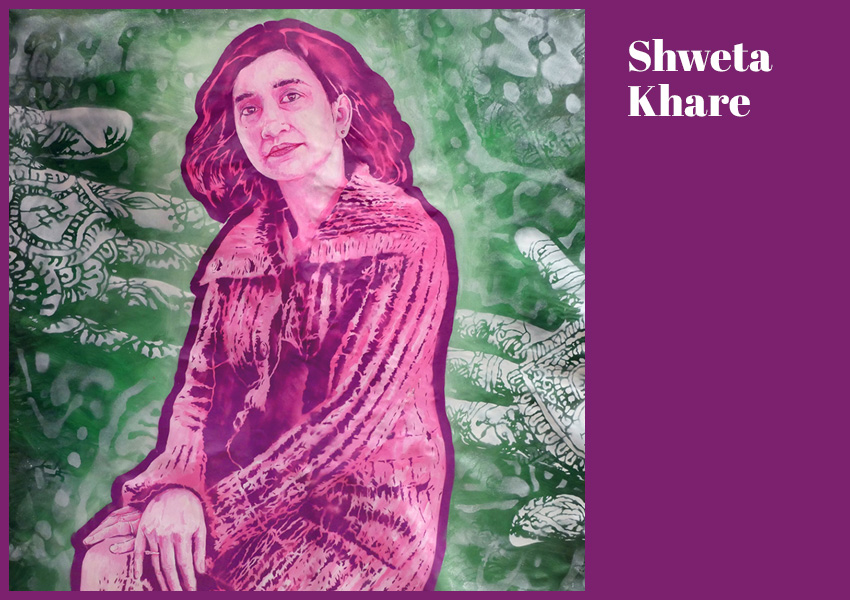

Shweta started to cry tears of joy when we surprised her back in February.

I interviewed her for about ten minutes under the pretence that I was an employee from McGill asking questions to mature students and their families. Shweta strikes me as someone incredibly grateful for the life she has, even if it’s not perfect. Family is so important to different Indian cultures, and her family loves her so much. My own mother moved to Canada and worked while raising a family in Vancouver. To do it all away from the familiarity of your home base is extraordinary. The spray-painted rendition of the henna designs in the background (that she created) is meant to elicit questions about what traditions we keep and what traditions we’re allowed to do away with.

——————

——————

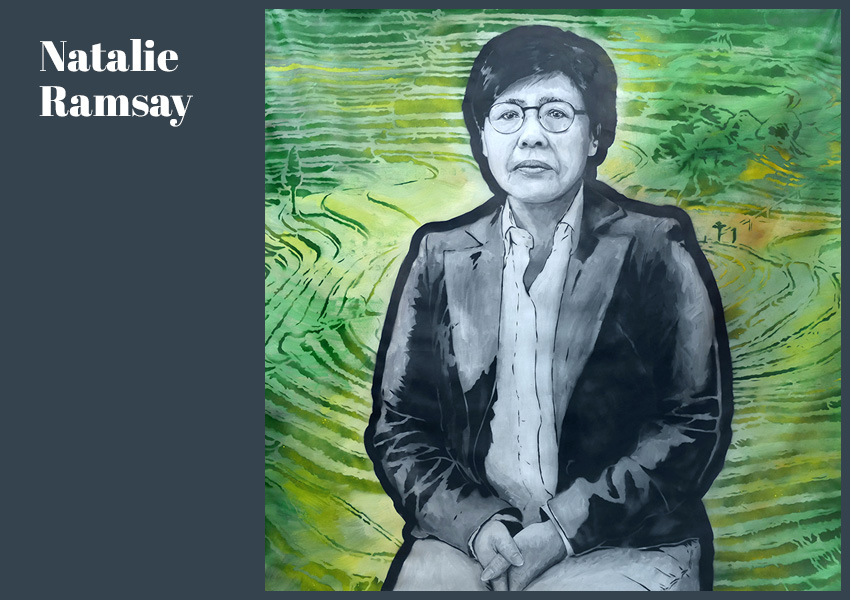

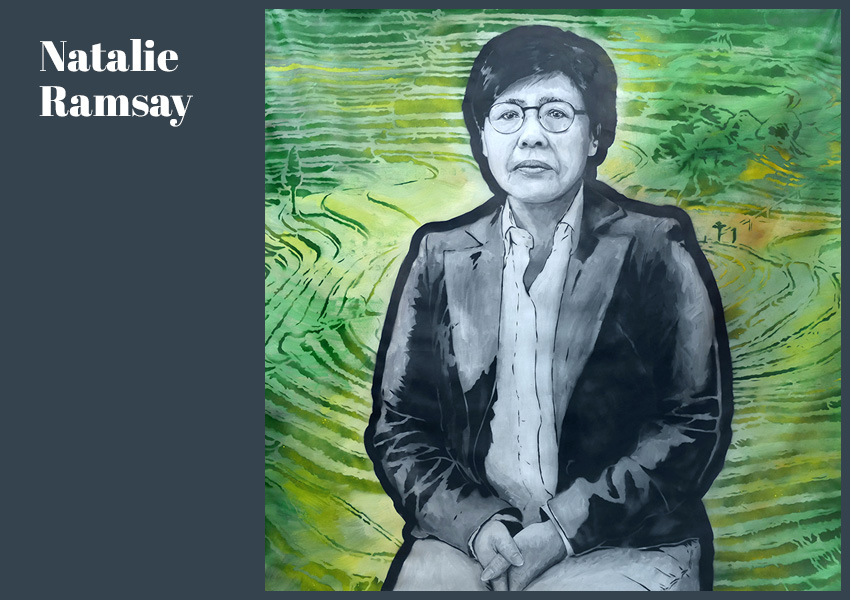

Natalie made a bold decision as a young woman; growing up in Rach Gia during the Vietnam War, she left her home country at 18, fleeing a communist government and the shadows of sexist marital expectations imposed by her traditional father.

She was nominated by one of her daughters, LeeAnn, who told me, “My mom (Natalie) used to tell me to ‘find a man who will help with the laundry.’ I didn’t get it when I was younger, but I get it now.” When she finally arrived in the United States, she built a life for herself as an electrical engineer, eventually switching to software engineering in Northern Virginia. Some of Natalie’s sisters still live the reality she left behind. She’s filled with pride wearing her blazer and going to work, far from the rice paddies of Vietnam that she never chose.

——————

——————

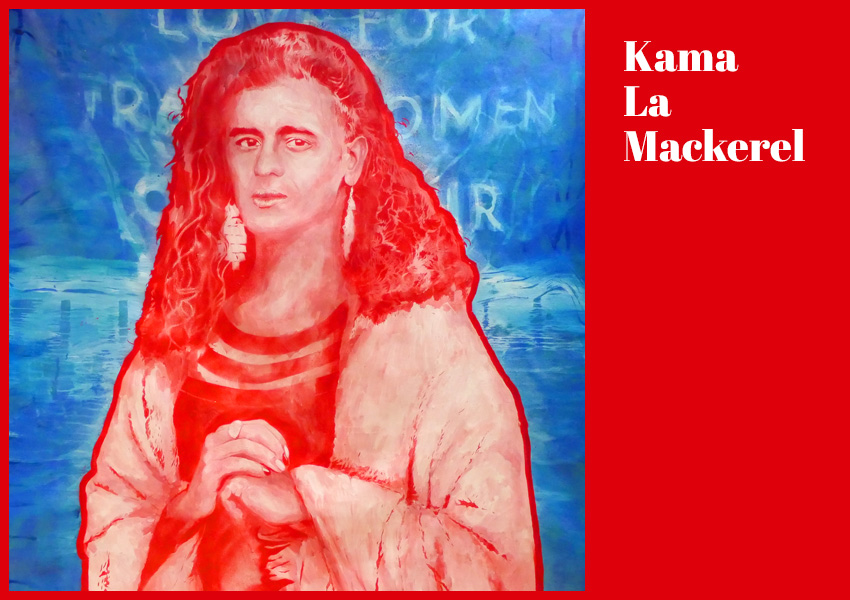

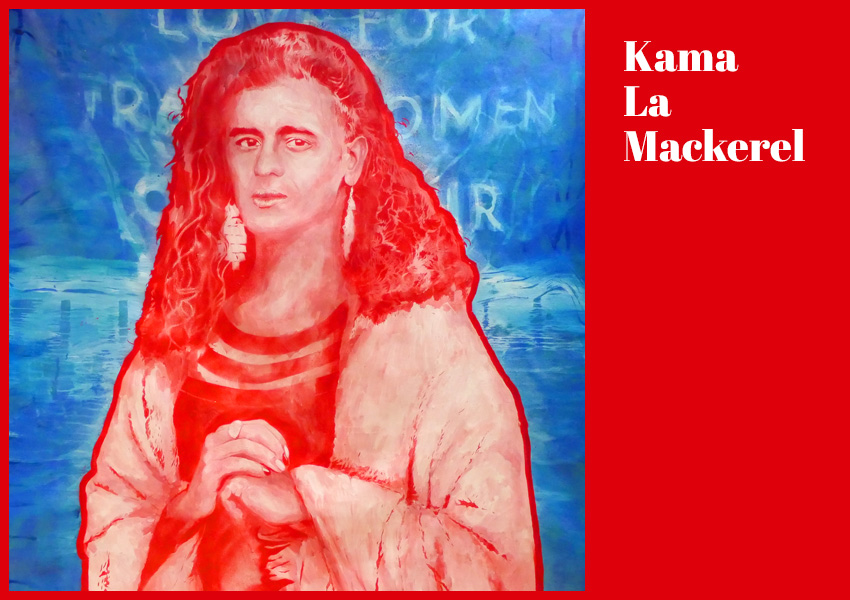

Kama has this amazing, boisterous and contagious laugh; they let the world know.

They often have a lot to say; their sentences flow into one another. Sometimes, I’m not sure where the personal ends and the persona begins. They are fabulous, and when it comes to style, they can definitely pull it off. Kama is an artistic ocean of art-making and storytelling; I really wanted to incorporate the positive, political assertions in their portrait by illustrating one of their banner objects in the background. They explain beautifully that their experience of gender is fluid, like waves of water – it comes and it goes, and it comes, and it goes.

——————

——————

Kathy is a tireless leader. She was nominated by two sisters in her community, Mona and Manel, who are understandably astonished about how she does so much.

She’s one of those people that uses the same 24 hours that everyone else has in some magical way. And with all of her commitments and responsibilities – working as a speech language pathologist or the Vice President of the Canadian Muslim Forum, or a workshop facilitator in her faith community on spirituality – Manel says you can still phone her at 2am if you’re in trouble, and she will answer the call. The fundraising slogan of the CHU Sainte-Justine hospital where she works, “plus mieux guérir” (meaning “heal better”), applied not only to her profession, but to her faith, and her life as a Muslim community member living in Montreal.

——————

——————

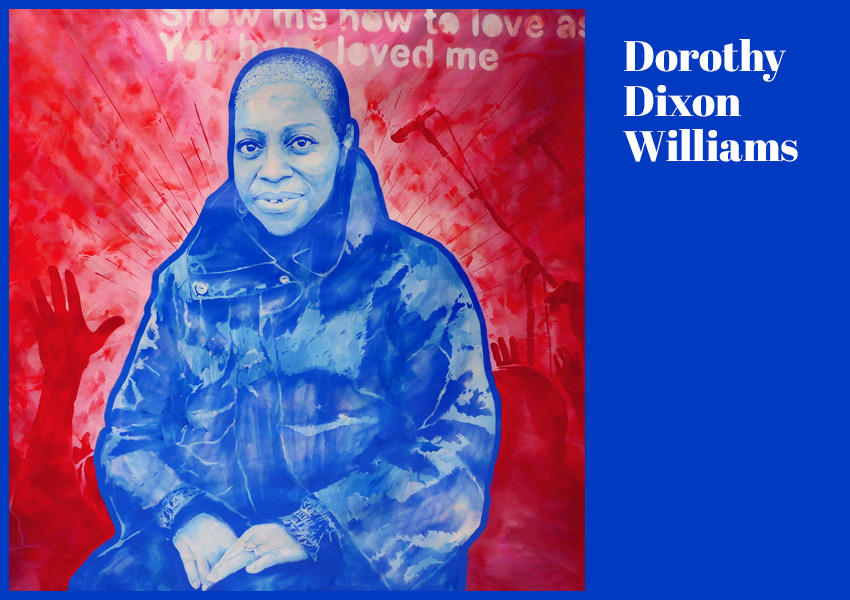

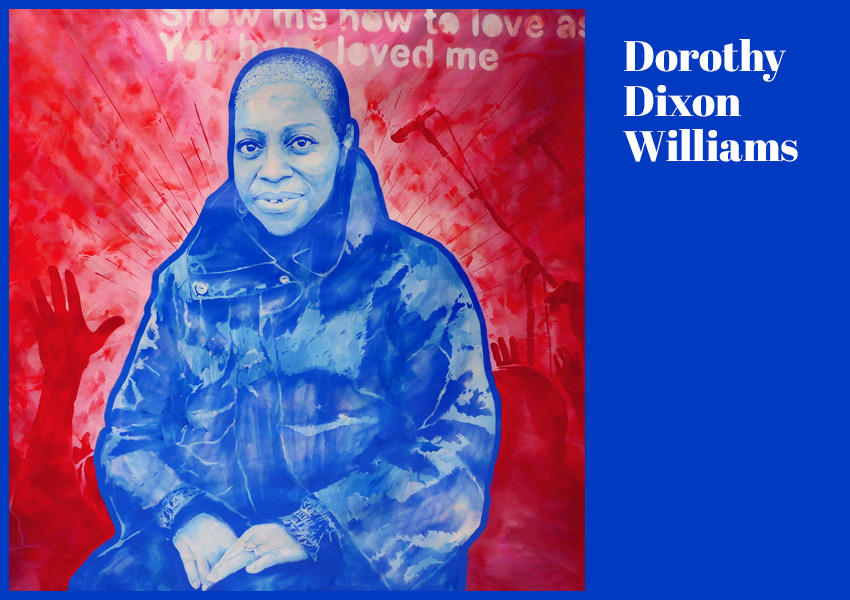

Dorothy grew up in the “cradle of the church” as she describes it. She doesn’t like small talk, likely because she values her time and the time of others enough to “go deep or go home.”

She still has a welcoming warmth about her that puts you at ease and makes you feel seen. She’s a pillar in her community. Dorothy was the only portrait that featured an open mouth – I wanted to capture her beautiful teeth while keeping in line with the strong, unapologetic tone of the portrait poses. Her portrait background highlights the role that faith plays in her life and how music often serves as the medium to express that devotion; the musical concert – with the lyrics as the centrepiece – represent the blurring of the religious and the everyday, of the personal and the political.

——————

——————

Clare is an amazing listener. She asks good questions. She seems willing to see the good in people.

(On our day together, she chatted with this loud barista who I thought was being obnoxious and crass – the kind of guy that yells across the room and calls women he doesn’t know “sweetheart.” She was really pleasant with him.) Her demeanour might be related to the fact that she’s the only daughter in the family with 7 brothers! Living in Montreal, walking in the Village, I think it’s easy to forget the struggles of queer peoples around the world. Clare is a great example of someone who does activist work not necessarily because she’s interested in abstract human rights and “politics,” but because she’s interested in her own survival.

——————

——————

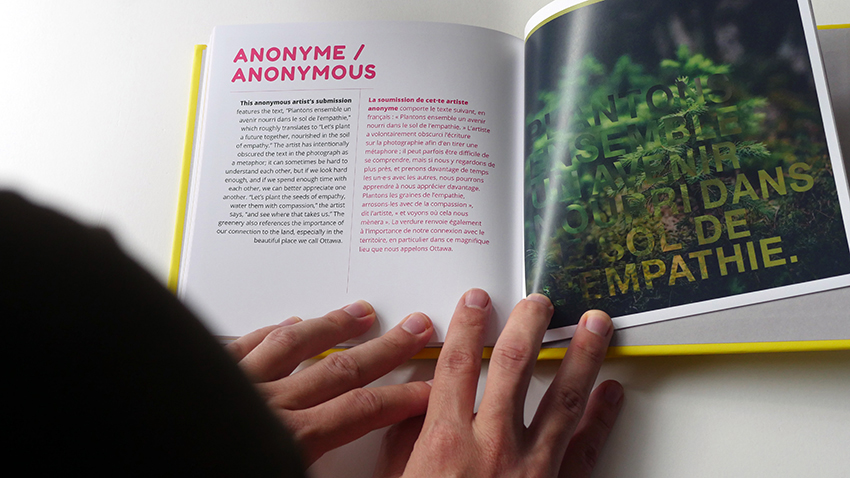

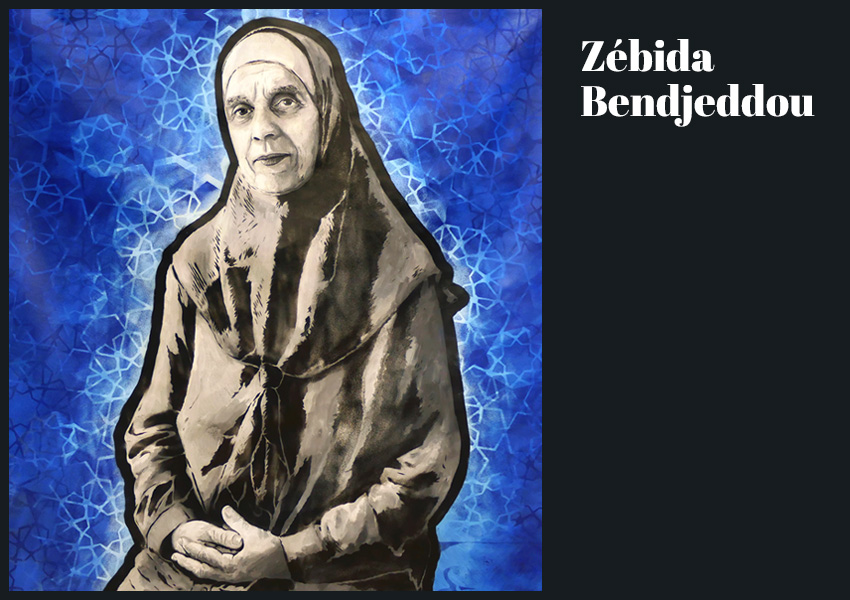

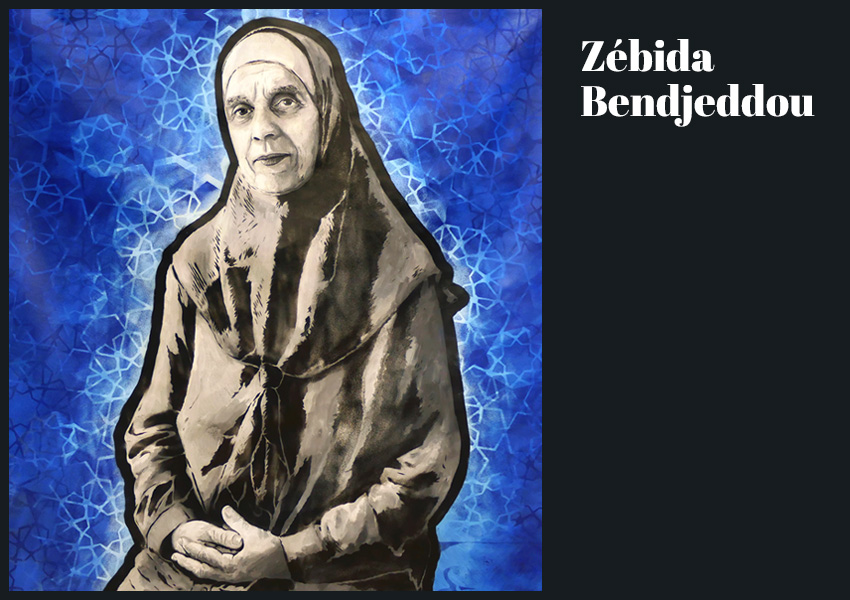

Zébida is a woman who commands respect. Her daily work seems grounded in her relationship with others, with herself, and ultimately, with God.

Zébida sees herself as apolitical, a simple volunteer for the good of the community. As I was leaving the mosque where we held the interview, I asked her what kind of art she likes; she said she used to draw stars and flowers as a child. A simple Islamic-style pattern felt fitting to contribute to the richness of the portrait while keeping true to the modest nature of her demeanour.

——————

——————

Joannie spends more time behind the camera than in front of it.

Her knowledge of photography made me a bit nervous to interview her and take reference photos for the portrait.I knew that she would notice the compositional choices of her artwork in a way that others might not. The home she has made with her partner Rumi felt like a treasure hunt of art projects. Joannie knows the opportunity she has as a teacher to shape the lives of her students. She is centred, both literally and figuratively, among the painted background that combines two of her passions in a symmetric way. The colour palette positions her against the stereotypical expectation of “girls wear pink.” I meant to include a subtle reference to an angel’s halo that emerges from the circular rings of the camera lens.

——————

——————

——————

Now, listen to the audio play created by Erin Lindsay as you visit with each portrait painting.

Learn more in the CelebrateHer online catalogue.

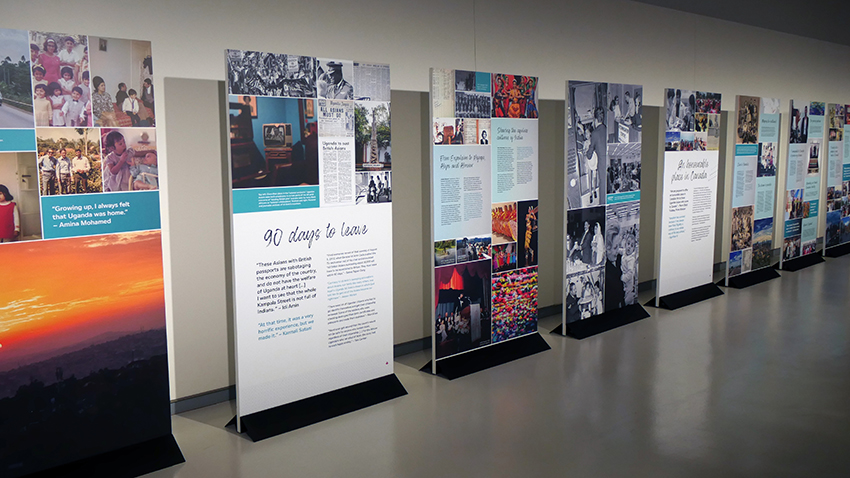

Click here to browse the catalogue in PDF format. Find process photos, biographies for collaborators Erin Lindsay and Micheline Chevrier, examples of written nominations, transcriptions of the audio play, installation photos from previous exhibitions, and much more.

——————

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

CelebrateHer was supported by a Digital Originals project grant.

Any questions? Email me.