Essay 1: Art as a Bridge: Aquil Virani and the Dialogue of Multiculturalism ––– by Tak Pham

Click here to see the printed version of the essay in PDF format.

Creating art within a community holds a unique power—an ability to forge connections, transcend boundaries, evoke emotions, and initiate meaningful conversations. For artist Aquil Virani, this practice is not merely a creative pursuit; it’s a calling deeply rooted in his multicultural upbringing. Born to an Indian father from Tanzania and a French mother, Virani’s journey led him from Surrey, British Columbia, to Toronto, Ontario, immersing him in some of the world’s most diverse communities. Drawing on personal experiences, Virani conceives and organizes community art projects that facilitate profound connections with immigrant communities, fostering understanding and empathy.

Virani’s art seeks to uncover commonalities among individuals sharing a common space, time, and resources, invoking the transformative power of art to bridge gaps and facilitate dialogues within a diverse society.

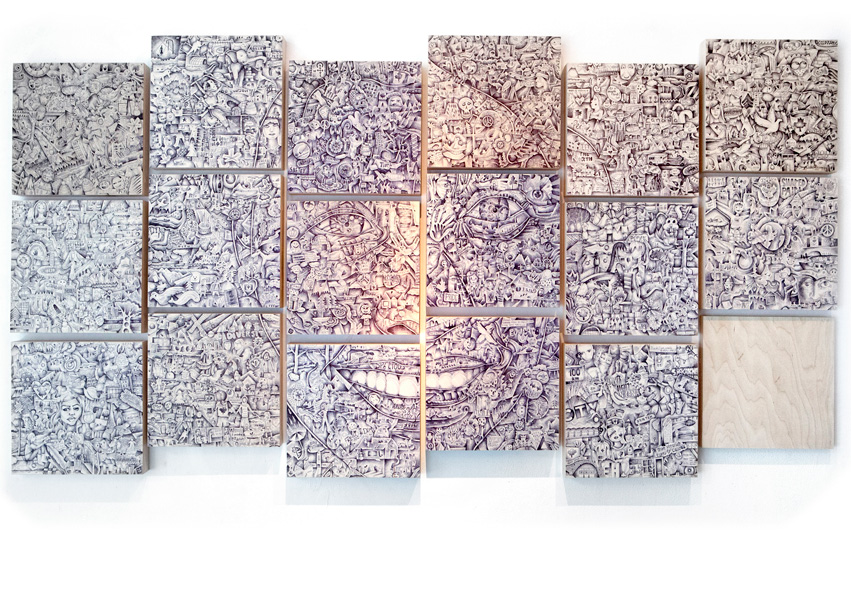

Virani’s approach to community art is characterized by his intimate connection to the communities he engages with. His multicultural background and upbringing have equipped him with a unique lens through which he views the world, allowing him to connect deeply with diverse communities. This closeness serves as the bedrock for his successful community art projects. At the core of many of Virani’s projects is the desire to discover common threads, shared understandings, and mutual sympathies among individuals within a complex society. Virani actively involves community members in the creative process, granting them a sense of ownership and belonging in the artistic journey. This approach activates art’s transformative potential, using it as a tool to transcend boundaries and spark meaningful conversations.One of Virani’s notable projects, Canada’s Self Portrait (2016), illustrates his commitment to creating art that fosters community dialogue and understanding. In this project, Virani engaged over eight hundred participants from Canada’s thirteen provinces and territories to create a collective portrait of the country. Beyond depicting a stereotypical “Canadian face,” this initiative aimed to showcase the rich tapestry of diverse identities and experiences that constitute Canadian identity. Canada’s Self Portrait resonated with audiences from various backgrounds, capturing the attention of the press and media.

Its ability to transcend cultural boundaries, evoke emotions, and initiate conversations about multiculturalism, diaspora, and citizenship made it a significant milestone in Virani’s artistic journey.

One can connect his work with other artists who explore similar themes from different perspectives to understand better the potential impact of Virani’s community art projects. Mass Arrival, a collective of migrant women of colour who are artists and professionals – including Farrah Miranda (artist, farrahmiranda.com), Graciela Flores-Mendez (legal worker), Tings Chak (artist, tingschak.com), Vino Shanmuganathan (law student), Nadia Saad (social worker) – offers a compelling viewpoint on multiculturalism. Their eponymous project, Mass Arrival (2013), focused on a recent history of Tamil migrants arriving in Canada and sought to revisit questions akin to those explored in Virani’s Canada’s Self Portrait project. The collective employed street theatre, public spectacle, and community organizing to commemorate the third anniversary of freighter ships carrying Tamil immigrants that arrived on the coast of British Columbia in 2009 and 2010.

In their re-enactment, hundreds of white-identified allies gathered outside Toronto’s Hudson Bay Company store and barricaded themselves with a satirical canvas replica of the ship MV Sun Sea. The project challenged the dominant narratives associated with “mass arrival,” which often evoke images of dark-skinned invaders in rusty freighter ships violating Canadian borders. Their work delved into themes of visibility and invisibility, historical erasure, and assertions of belonging. The project posed a fundamental question: Who has the moral legitimacy to decide who belongs in the settler colonial nation-state? While some arrivals are celebrated as the foundation of national creation stories, others are met with fear, hysteria, and tightened border control. Virani’s and Mass Arrival’s projects aimed to provide concrete profiles that underscored the complex issues surrounding multiculturalism in Canada. However, while Virani focused on collaborating with specific marginalized groups, Mass Arrival’s critical lens sheds light on broader issues from a different perspective.

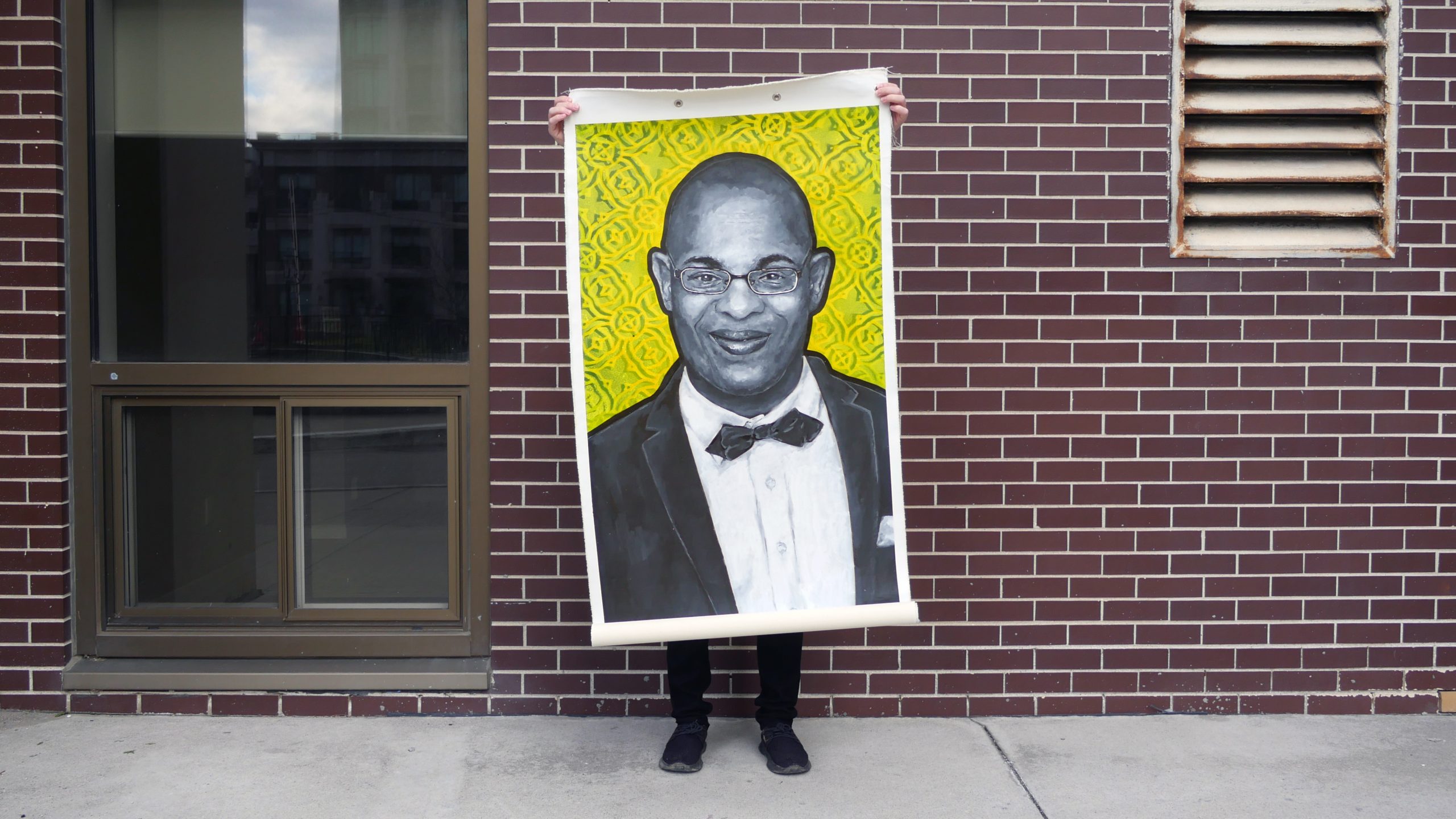

January 29 (2022), one of Virani’s most poignant projects, is a robust response to a tragic event that unfolded on January 29, 2017, when six Muslim men were brutally murdered at the Centre Culturel Islamique de Québec in Quebec City. This project, supported by the Silk Road Institute , a Montreal-based Muslim arts organization, along with charitable organization TakingITGlobal, and the Government of Canada, features six large-scale portraits of the victims. As a direct commemoration of the horrific event, the project features portraits depicting the men in stoic poses reminiscent of community.

The stark contrast between the black-and-white portraits and the vibrant geometric backgrounds, featuring Islamic mosaic motifs, symbolizes the resilience of the community in the face of such atrocities.

January 29 serves as a remembrance, a reflection, and a call to action, urging viewers to contemplate the lives lost and the impact of Islamophobia on Muslim-Canadian citizens. The project highlights the gaps in understanding and the apathy between different segments of Canadian society. It exemplifies how art can be a powerful tool for healing and bridging divides within a community.

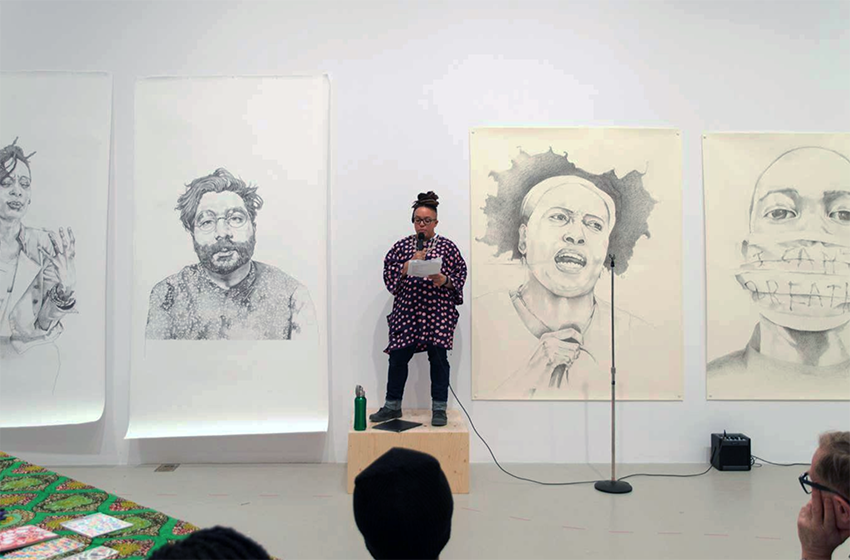

To further explore the impact of community-based art projects, we can draw parallels with Syrus Marcus Ware’s Activist Portrait Series (2016—ongoing). Ware, a Canadian artist and activist, creates larger-than-life portrait drawings that honour activists from various communities, including Black, Indigenous, Queer and Trans, and Disability communities. Ware’s art demands a considerable level of appreciation from viewers. His drawings, some as tall as ten feet, command a monumental presence in their exhibited spaces. This presence draws viewers in, inviting them to engage with the subjects and inquire about their stories. Ware’s work bridges the historical portraits of aristocrats and social elites often discussed in Western art history classes and the present-day activists who shape our society.

Virani’s and Ware’s projects have a shared goal of demanding attention and respect for subjects who often go unnoticed or underappreciated in mainstream discourse. They create art that becomes a part of the history of the present, capturing the essence of contemporary struggles and activism.

Virani’s project January 29 also includes a documentary by filmmaker Adrijan Assoufi, providing insights into Virani’s creative process. In the film, the artist is seen visiting culturally and politically significant places in Quebec City; the artist unrolls the portraits and proudly exhibits the men in locations that could have been hostile to them. This strategy aligns with Mass Arrival’s demonstration of human bodies en masse, creating interventions in public spaces. Both projects aim to disrupt the status quo, challenging how Western society moves through and past news about marginalized communities.

The community art projects from Virani exemplify the transformative power of art within communities. His multicultural background, personal experiences, and intentional engagement with communities allow him to create art that forges intimate connections, transcends boundaries, evokes emotions, and initiates meaningful conversations.

Virani’s projects go beyond mere artistic expression; they inspire change, empower community values, and provide transformative experiences for individuals.

By placing Virani’s work in context with other artists’ practices, such as Mass Arrival and Syrus Marcus Ware, we gain a deeper appreciation for how community art challenges conventional perceptions of multiculturalism and fosters empathy and understanding among Canada’s diverse communities. Virani, Mass Arrival, and Ware are all catalysts for change, using their art to bridge gaps and create a sense of belonging among marginalized communities. Virani’s commitment to creating art that connects, inspires, and transforms is a testament to art’s enduring and transformative power within communities.

Through his work, he not only celebrates the vibrant tapestry of multiculturalism but also confronts the complex issues that arise within this diversity.

Tak Pham (he/him) is a Vietnamese contemporary art curator and writer. He is currently curator of the Illingworth Kerr Gallery at the Alberta University of the Arts in Calgary, Alberta, Treaty 7 territory. He was formerly associate curator at the Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina, Saskatchewan, Treaty 4 territory. Pham holds an M.F.A in Criticism and Curatorial Practice from OCAD University and a B.A. Hons. from Carleton University. He has curated exhibitions and organized curatorial projects for the MacKenzie Art Gallery, Contemporary Calgary, Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Varley Art Gallery, Art Gallery of Ontario, and Nuit Blanche Toronto, among others. His writings and reviews have appeared in Canadian Art, C Magazine, ESPACE art actuel, esse arts + opinions, GalleriesWest, Studio Magazine, ArtAsiaPacific and Hyperallergic. In 2023, Pham was awarded the Hnatyshyn Foundation-Fogo Island Arts Young Curator Residency. Pham’s curatorial projects have been featured on Canadian Art, Akimbo, Artoronto.ca, Blouin Artinfo, CBC Arts, Cultre Magazine, Leader Post Regina, The Prairie Dog and NOW Toronto. @takpham

Acknowledgements: The production of this essay was supported by a grant from the Ontario Arts Council; it contains artworks that were produced with funding from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, the Silk Road Institute, Imago Theatre, TakingItGlobal and the Government of Canada.

Essay 2: Aquil Virani celebrates the stories of everyday people ––– by Devyani Saltzman

Click here to see the printed version of the essay in PDF format.

In Aquil Virani’s current work-in-progress, Unpacking Ismaili Baggage, 1972 (2022), a portrait of a man in a suit is painted amidst a western landscape on the inside cover of a vintage suitcase. The portrait is in black and white, the background in colour. The worn leather invokes nostalgia, longing and displacement. A second work in the series depicts women marching in Tanzania, also in black and white, a sole woman in kaftan, Virani’s paternal grandmother, in colour in the foreground, a plane at altitude in the distance. The series depicts the mass migration of Ismaili Muslims from East Africa, headlined by Idi Amin’s 1972 presidential decree that nationalized the property of “Ugandan Asians” and forced tens of thousands to flee to largely commonwealth countries, including Canada.

The series, commissioned on the 50thanniversary of the 1972 expulsion, touches on a number of themes that run through Virani’s work – documentary, portraiture and themes of belonging and displacement.

Virani, who was born in Canada and raised in Surrey, BC with an Ismaili father of Indian origin from Tanzania and a French mother, speaks of his work as “crafting narratives and doing things that documentary photography can’t do.”

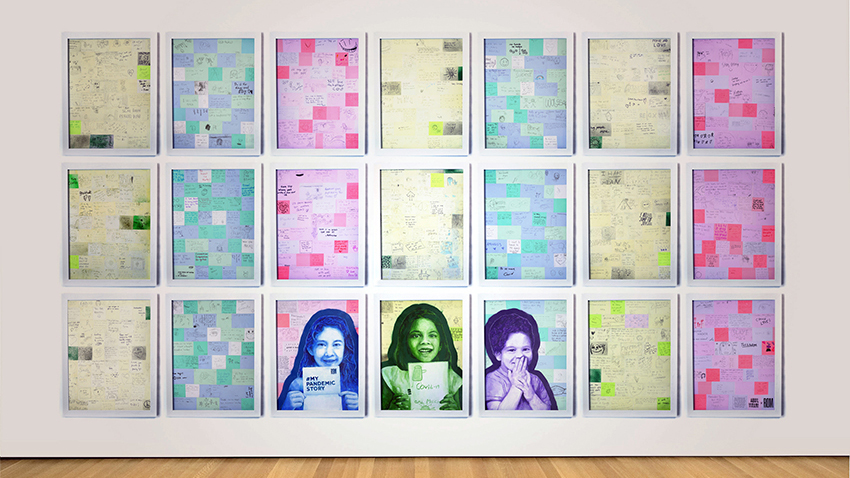

In another series, Our Immigrant Stories (2022), six works depict portraits of people from across the country now called Canada. Their images are painted in colour against a background of text telling their stories. The works sit alongside a nine-minute film and a book of one hundred additionally-submitted accounts.

Created while artist-in-residence at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Halifax, the series illustrates another key aspect to Virani’s practice, and possibly what is at the core of his work: the stories of everyday people, and their active participation in sharing their narratives.

The everyday voices of individuals shared through participatory portraiture is a unique and beautiful community-based practice. When asked “why portraiture?,” Virani responds that he is “drawn to human faces” and he believes “strongly in making work that is relevant and emotive for an audience. The best way to connect is through portraiture, because we are humans, drawn to other humans, putting people at the centre of our stories.”

Our Immigrant Stories highlights the large-scale collaborative art-making that is at the centre of Virani’s practice. Participants were invited to submit stories digitally and respond to the prompt “Who are the immigrant heroes in your life?” A daughter’s words about her mother, a nurse in Vancouver, are amplified via collage. A grandson reflects on the challenges of his grandmother’s arrival in Canada. Virani works in acrylic and spray paint – and more recently, short films, graphic design and installations. He cites growing up as the youngest child of a single mother after his parents divorced, time spent alone to draw, and the encouragement of a high school art teacher as foundational.

When asked how his upbringing as a mixed-race son of immigrants influences his work, Virani highlights it’s why he desires an art practice that involves people and uplifts a diversity of experience. It’s why he wants his art to contribute to social change movements. “Three pillars guide my evolving artistic practice: accessibility and participation, social relevance, and representation.”

Maybe one of the most powerful examples of this is Les portraits commemoratifs en espace public (2019-21). The portraits are commemorations of the six men who were killed in the Quebec City mosque attack on January 29, 2017. Virani was invited to create the series by the widows, one of whom saw his work online and reached out to commission him. The resulting works are powerful large-scale portraits, which Virani then held in public space throughout the city and documented via photography before gifting them to the families. Alongside the portraits, he created 29 messages for Quebec, a limited-edition book, crowdsourced from the public all over the world and illustrated using stencils and black spray-paint.

Over many years, he has built a relationship with the Mosque and the families, but Virani notes that he is still very much an outsider in the Quebec City Muslim community, given the cultural and sectarian differences between them. When asked about how his own Muslim identity influences his work, he responds that he has a tough time answering that question. “Honestly, it’s hard because it’s impossible for me to separate what I gleaned from culture vs. religion. Ismailism is a religious community, but it’s also a cultural community. When I learn from my family, my aunts, my uncles, is that part of my religious education?”

What Virani’s body of work speaks to, in addition to participatory practice and portraiture, is a form of “subtle activism” rooted in seva, the ethic of selfless service, which is a tenant of Ismaili faith and practice. His projects are rooted in building empathy and inspiring change through listening to experience. “When I do participatory projects, I’m a facilitator, trying to stay true to the stories I’m entrusted with.” Along with this ethic comes necessary questions in relation to the nature of allyship.

In CelebrateHer (2018), Virani painted twelve publicly-nominated women in a feminist portrait series and audiovisual installation, created in collaboration with Montreal’s Imago Theatre. It includes images of Indigenous leaders as portrayed by a settler artist. He’s deeply cognizant of representation and in our conversations asks himself, “Are you centering yourself? Or doing things the right way?” He notes that he is not an immigrant either and many of his projects involve newcomers. “I think about that a lot. How to act in solidarity.”

Alongside questions of solidarity, and collaborating to represent the stories of others, Virani reflects on pathways for newcomer artists, citing access issues to the art world, including lack of long-standing networks in Canada and art school as a common gateway (noting he himself did not go to art school). “All these issues are exacerbated if you are coming from afar. And in the public art world, museums, if you’re not yet immersed in a culture, you’re not yet immersed in the zeitgeist, and may not be hitting the ‘it’ topic that public spaces are interested in. Artists who face barriers are often pressured to make work about those barriers, about identity. Even in grant applications, I feel pressure to ‘Muslim it up.’”

Despite the challenges and expectations of the systems we operate within, Virani’s work is a rare collaborative commons where everyday stories are heard and shared, shaped by colour and form, and ultimately given back to community in the spirit of solidarity and seva. In a world increasingly divided, he continues to listen.

Devyani Saltzman (she/her) is a Canadian writer, curator, and arts leader with an in-depth practice in multidisciplinary programming at the intersection of the arts, ideas, and social justice. She was most recently Director of Public Programming at the Art Gallery of Ontario, one of North America’s leading art museums. Saltzman was previously the Director of Literary Arts at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, as well as a founding Curator at Luminato, Toronto’s international multidisciplinary arts festival. She is the author of Shooting Water which The New York Times called “a poignant memoir.” Her work has appeared in The Globe and Mail, The Atlantic, Room Magazine, and Tehelka, India’s weekly for arts and investigative journalism. Saltzman has a Masters in Anthropology and Sociology and is currently working on her second book of nonfiction. @DevyaniSaltzman

Acknowledgements: The production of this essay was supported by a grant from the Ontario Arts Council; it contains artworks that were produced with funding from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, the Silk Road Institute, Imago Theatre, TakingItGlobal and the Government of Canada.