Artist Aquil Virani’s collaboration with the ROM

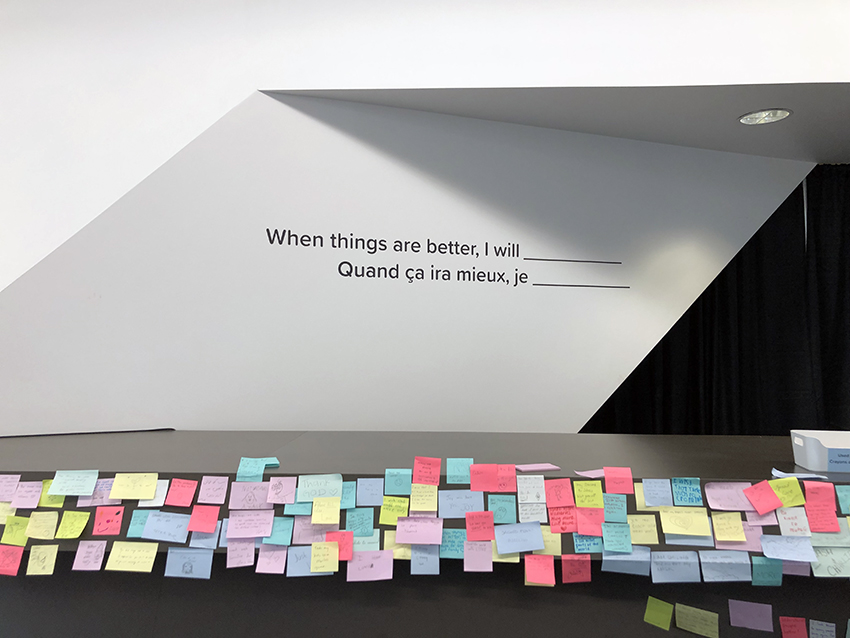

Last year, the ROM’s #MyPandemicStory exhibition included a “response station” where visitors were invited to write responses to the prompt, “When things are better, I will…”

With the help of ROM curator Justin Jennings, Toronto-based artist Aquil Virani integrated hundreds of these sticky notes into a multimedia artwork, commemorating our collective early pandemic experiences and amplifying the diverse voices of participating community members. Read a Q&A with the artist below.

To begin simply: what is the project about?

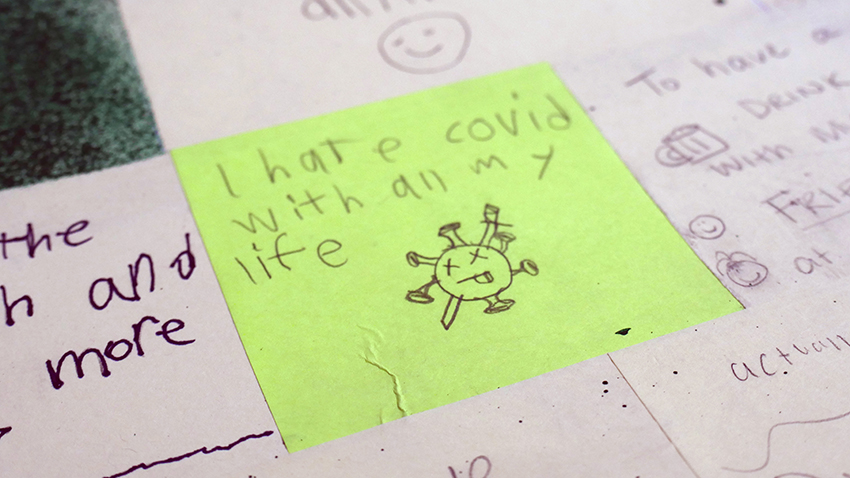

“Things will get better” is a large-scale multimedia artwork, built with community submissions to mark this moment in time and promote a sense of optimism for a better future. The participatory responses – written by ROM visitors – reflect a variety of valid pandemic experiences, frustration, anxiety, denial and human resilience.

Any notable things that visitors wrote? Things that surprised you?

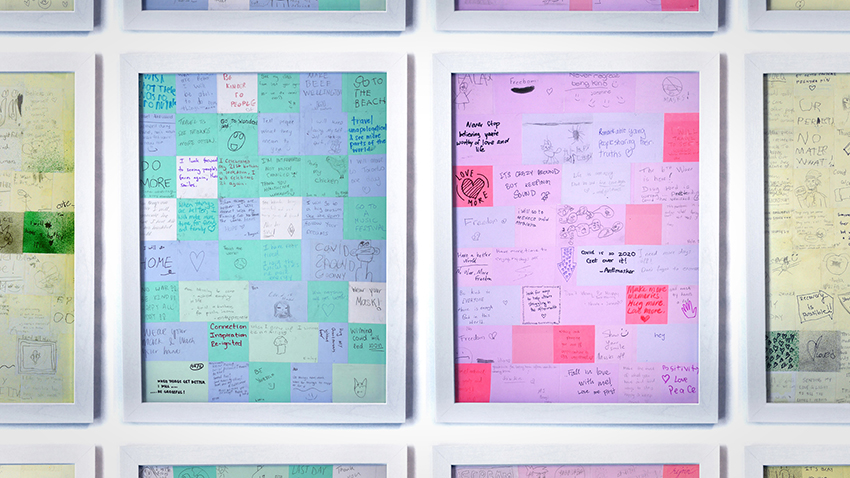

So many interesting thoughts! To give you some examples, the sticky notes said, “When things get better, I will… Scream into a pillow; Re-join Tinder; Make art about it; I will jump for joy!; Still love each other; je veux visiter ma grandmère; travel unapologetically; hug my grandparents without fear; look for ways to help others struggling in the aftermath.” They also said things like: “No more covid pls!; This too shall pass; Next week, no more masks!; Remember you are always loved; Online school sucked and I felt like I missed out on so much; Stay strong; Do it for Future You! ”

Did you have to censor any of the sticky notes?

For my community-engaged projects, I like to feature most submissions – unless they’re hateful, harmful, or inappropriate in nature. As a good “test case,” there was a sticky note that read “Left wing propaganda!” likely in reference to the pandemic. I included it, even if I disagree with the vague insinuation. I love that participatory art can act as an insightful mirror of society. I think it’s important to include some sticky notes like that one – to document the times.

—————— “When people came to #MyPandemicStory, many shared their hopes for the future on sticky notes. Aquil’s artwork does an amazing job of using those notes to both capture an important moment in Canadian history and help chart our way forward in a post-Covid world.” —– Justin Jennings, ROM Curator of the #MyPandemicStory exhibition

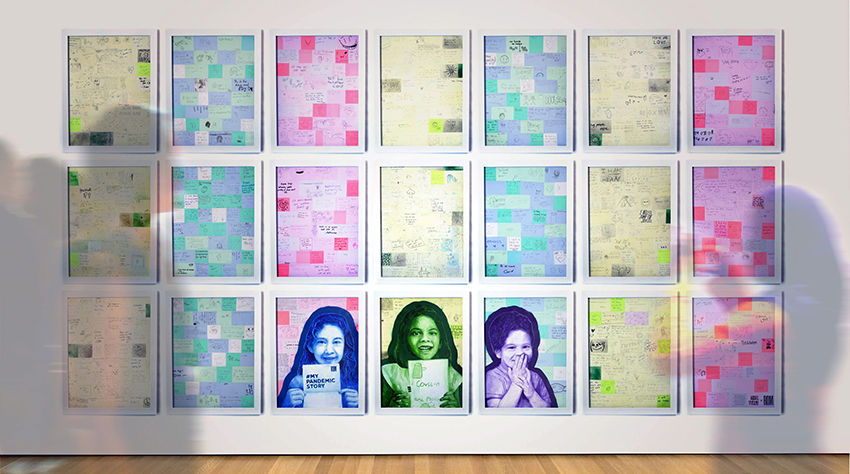

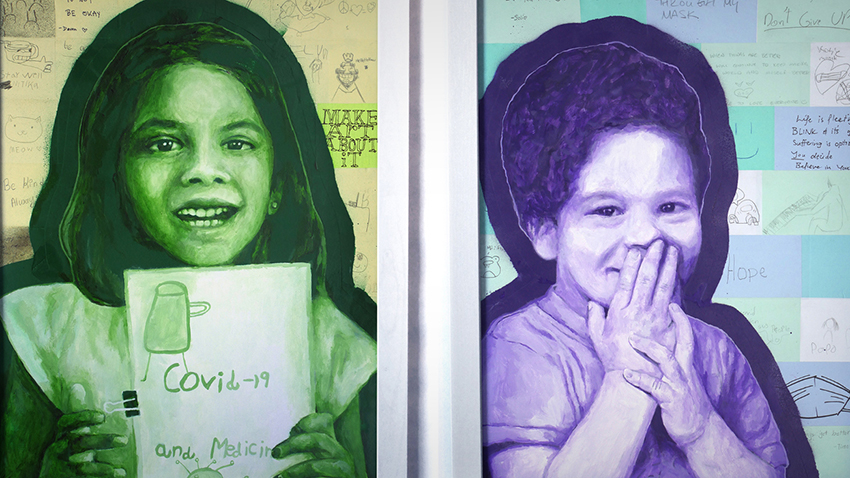

Tell us about the painted portraits.

I think deeply about who to represent and how to represent them. The central portrait, for example, features Nitika – an exhibition participant who submitted a video story titled “COVID-19 and Medicine.” Because the ROM’s prompt suggests a sense of optimism — “When things get better, I will …” — I wanted to feature different youth looking happy, enjoying themselves. We don’t want to “paint over” the damage and suffering of the pandemic, but it’s important to dream of a better future sometimes. I made sure to get parental permissions before representing the youth depicted.

How big is this thing? How many stickies?

The artwork is presented on 21 different panels of thick paper, each 18 x 24 inches, displayed in a 3-by-7 grid. In total, that’s 6 feet by 10.5 feet. The panel format allows me to work on a manageable surface at any one time and transport the larger artwork easily. I estimate there are roughly 750 sticky notes included in total.

You’ve described this artwork as a “community time capsule.” Why is that?

In a way, any art is a time capsule because it can express a specific thought or feeling at a particular moment. And this artwork features multiple perspectives indicative of hopes, dreams and anxieties during earlier pandemic times. In a written piece published in Living Hyphen Magazine this year, I designed a “letter to the future” activity within the publication for people to enjoy; I urged people to “play with the magic of time” since even a simple letter can take on meaning and sentimental value simply because it is “from another time.”

How does this project fit in with your other work?

I often integrate public participation into my art projects. And I like to explore interesting and socially relevant questions. In 2014, for example, I travelled from coast to coast with collaborator Rebecca Jones to collect over 800 drawings about Canadian identity from all 13 provinces and territories. I re-produced each of the doodles into a single art piece titled “Canada’s Self Portrait.” In 2020, I produced a book of 29 crowdsourced messages of hope and solidarity dedicated to the Quebec City Muslim community after the terrorist attack on January 29, 2017. During a recent artist residency at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, I created a short film that integrated photographs and text from publicly-submitted stories of “the immigrant heroes in our lives.”

Have you worked with sticky notes before?

Indeed, at MuralFest in Montreal in 2017, for example, I made a smaller artwork with sticky notes. I didn’t group them by colour though, and the result ended up a bit unharmonized for my liking. I also created a large-scale mural at Southridge School in Surrey, BC in 2020, just before the pandemic took over. We used white sticky notes that I unified with splashes of colourful acrylic paint.

Why do you often make your projects participatory in nature?

I have things to say, but I also know that others do too – and I want to hear from them. I think participatory art often results in a work with depth – something engaging that you can look at for a long time, discovering all of the little treasures hidden throughout the artwork. I want to embed the idea of “multiple perspectives” into the art itself. We live in a society with other people, and the conversation is always richer with more people at the table.