Your Memoir

Cliquez ici pour lire en français.

“What would be the title of your imaginary memoir?”

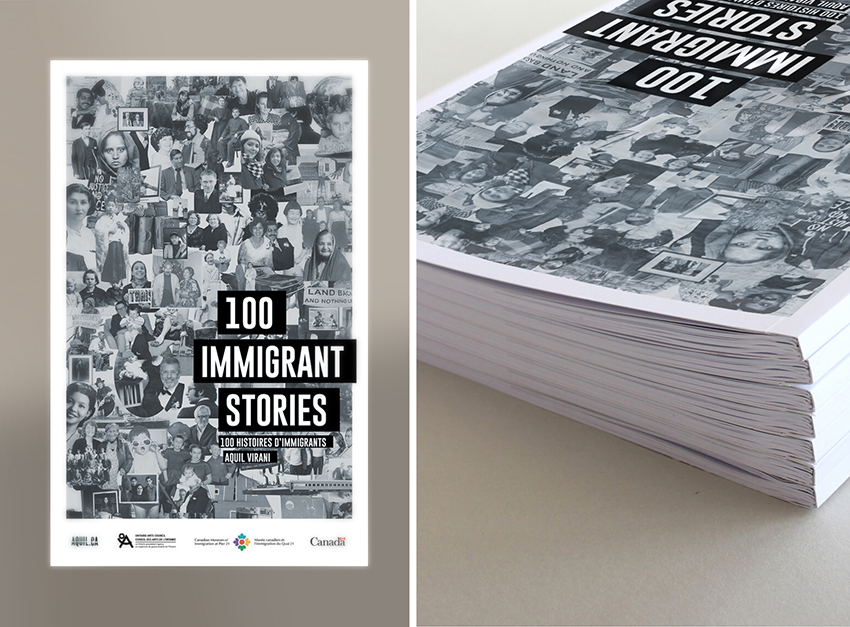

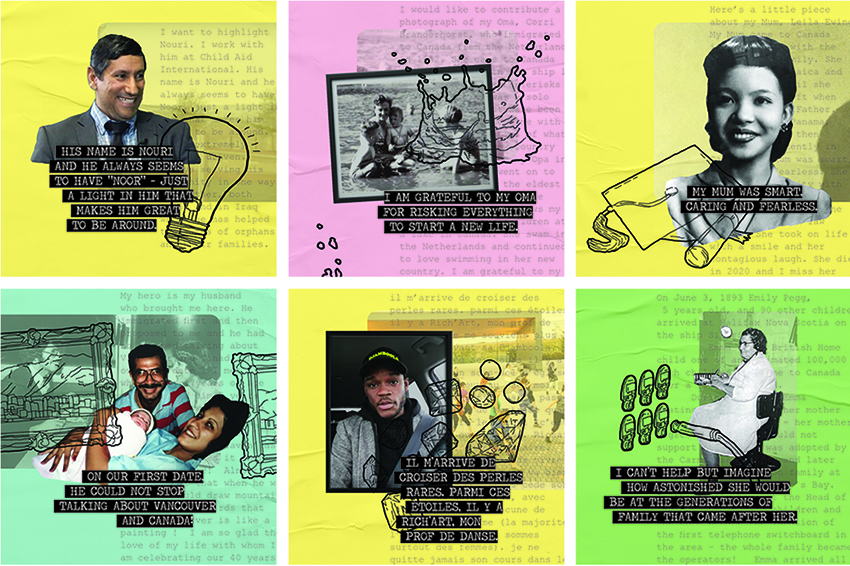

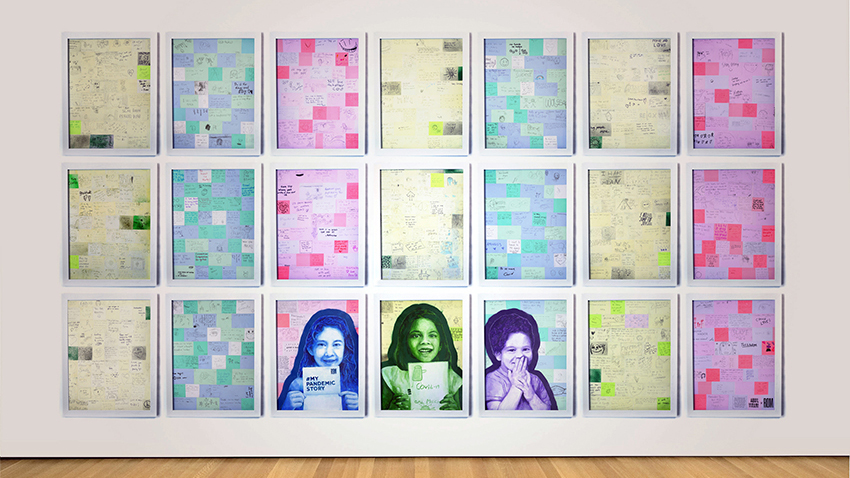

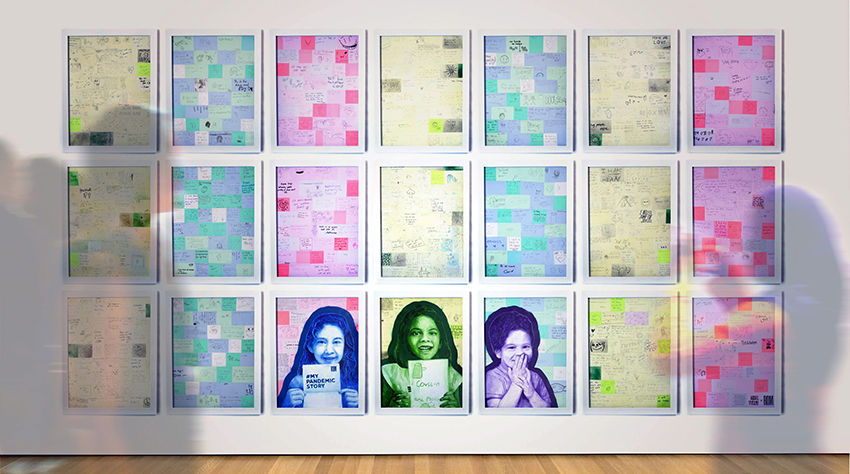

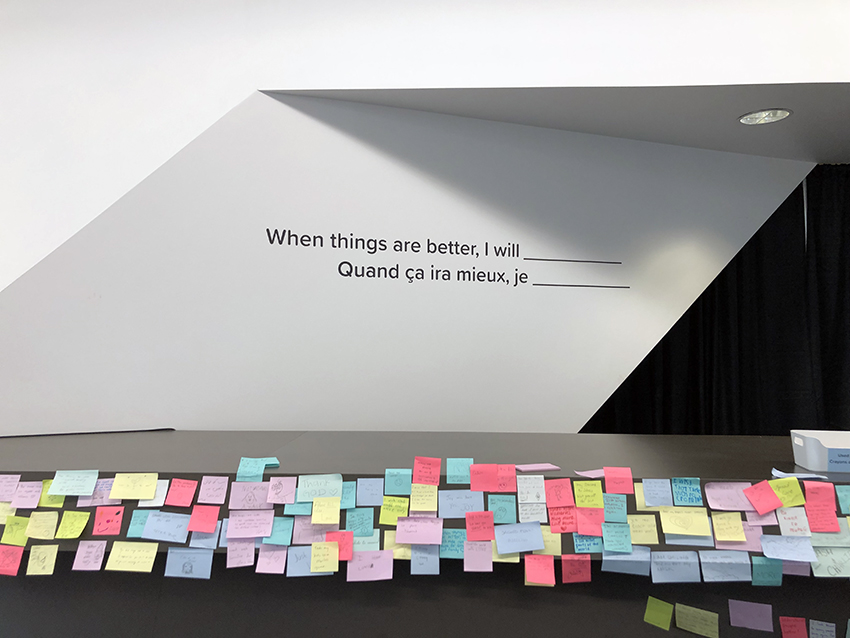

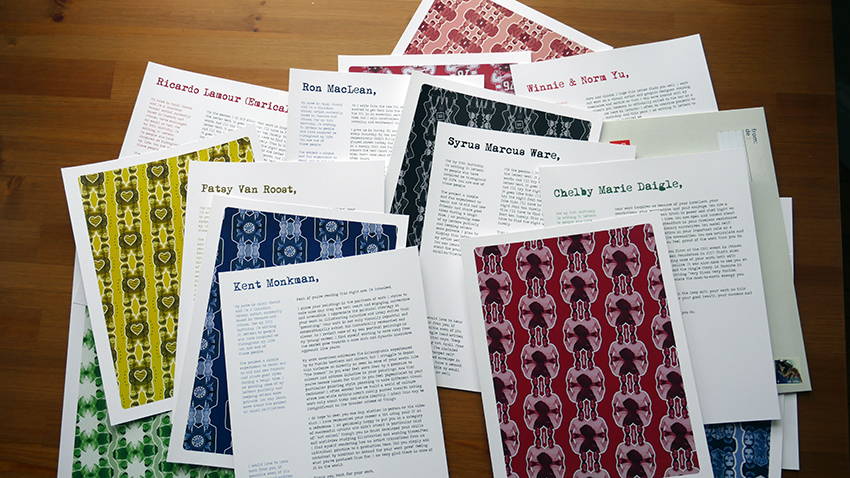

I believe we all have a story worth telling. And so, I asked the public for “the title of your imaginary memoir” and created book cover designs using that submitted text. I wanted to celebrate the stories in each person that make us each unique. We may not be famous movie stars, but our story is worth writing down.

I often encourage everyone – friends, family, the public – to be creative and tell their story. This project tells everyday people: “You have a story. We are interested in your story. You just have to share it with us.”

What do you like most about designing book covers?

There’s the creative challenge of telling a story with a few words in a title and a singular image. There’s the creative challenge of standing out in the same-sized rectangle of twenty other books on a shelf. And there’s an “accessibility” (or ease of connecting with the average person) when there’s a mix of text and image; anyone who can read English can understand the title and glean something from a title and a book cover.

This is your 10th birthday art project. What other projects have you done over the last decade?

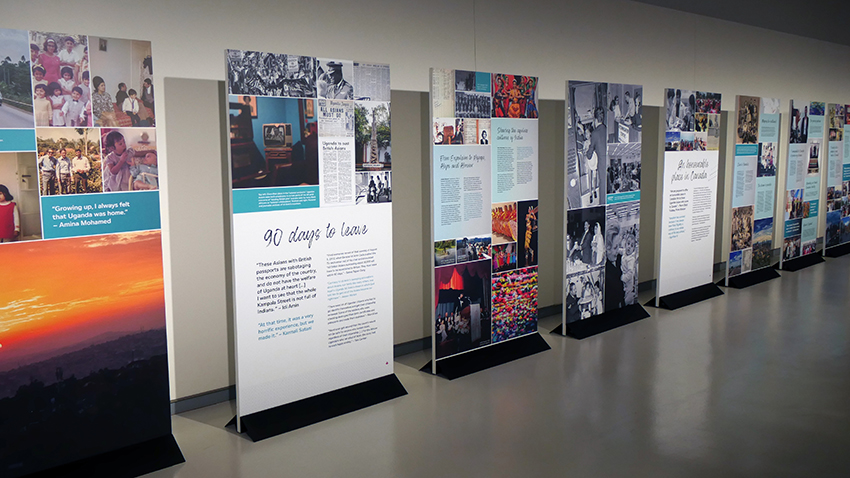

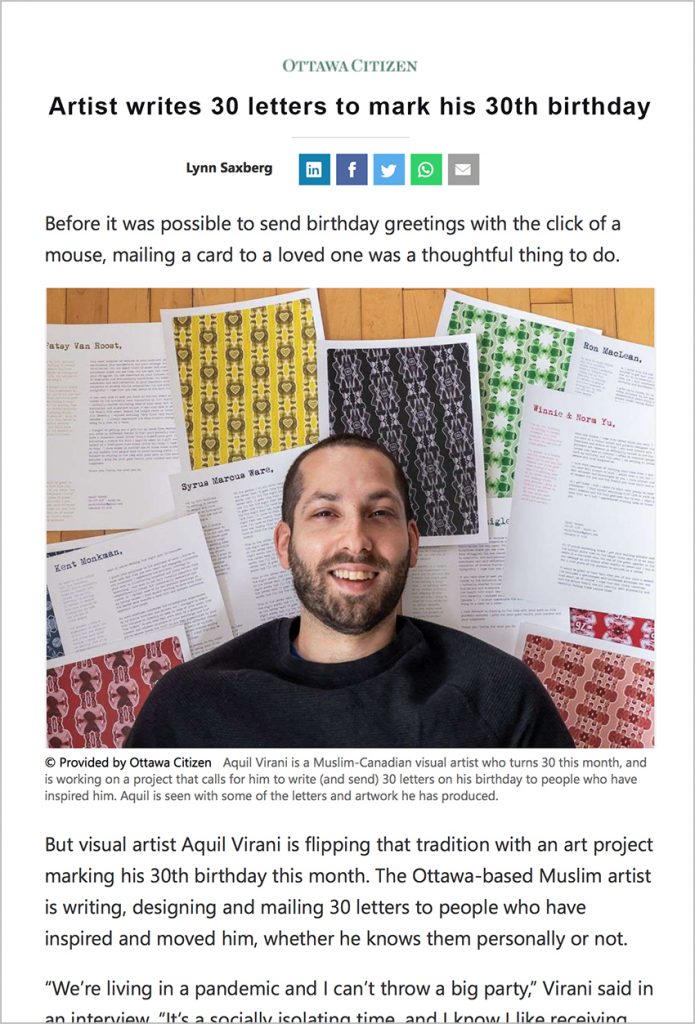

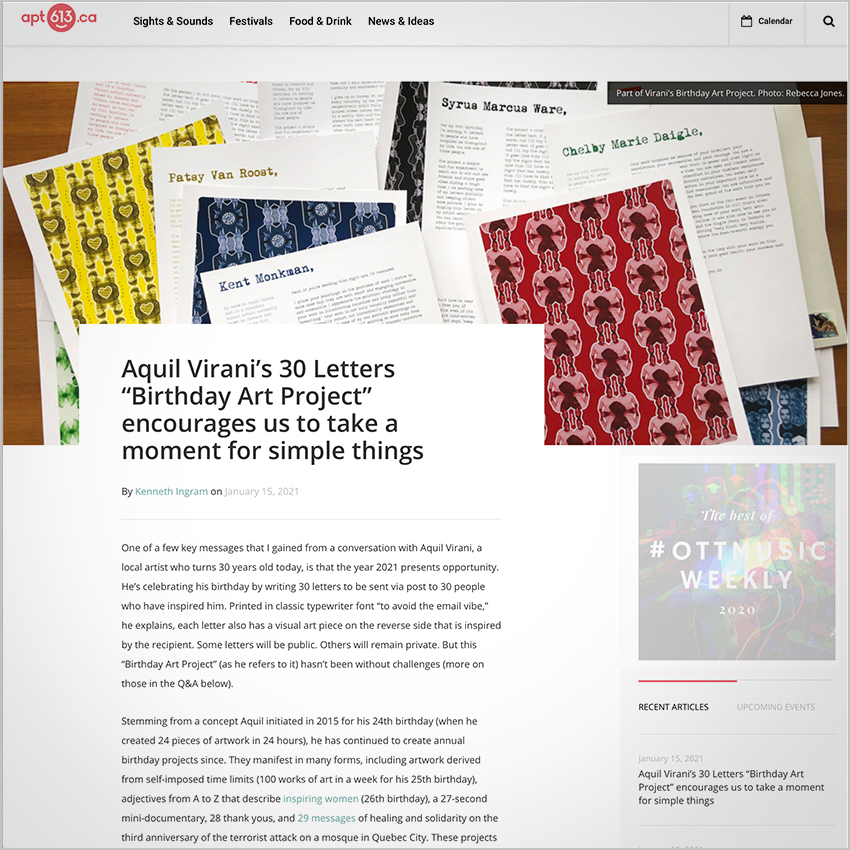

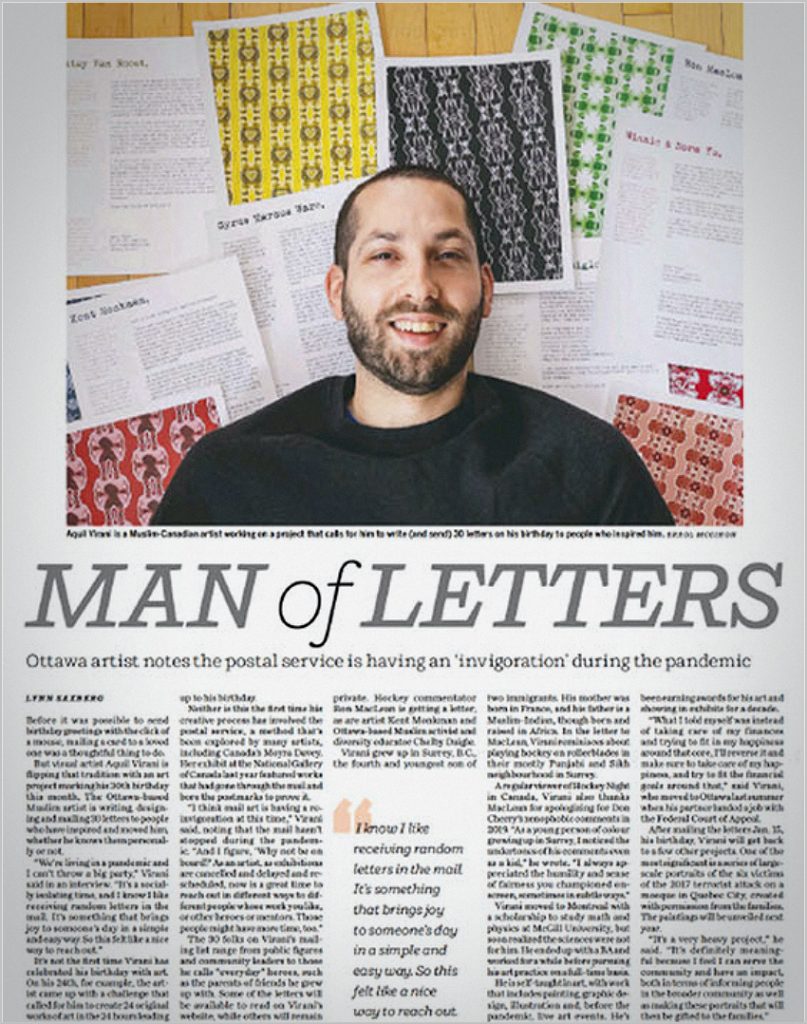

Last year, I shared 33 “hospital delights” or moments that brought me joy during my two separate month-long hospital visits. A couple of years ago, I collected “32 hard questions” that I answered online. Other projects have included 100 artworks in 1 week for my 25th, a series of art prints with 26 adjectives that describe inspiring women, a video of 27 seconds with queer activist Clare Byarugaba as part of the CelebrateHer project, 28 thank-yous, 29 illustrations for the Quebec City Muslim community, 30 letters to heroes and unthanked role models from my childhood, and 31 immigrant stories from my artist residency with the Canadian Museum of Immigration.

What are some things you consider when designing a book cover?

First, there’s the legibility of the design choices – can the title be read and understood without the design “getting in the way”? I also think about the design principle of hierarchy, meaning “where do people look first? What is the focal point?” If everything on the cover is shouting, you won’t hear anything. Obviously, I’m trying to pique the viewer’s interest while communicating the overall story. “Does the design reflect the overall tone of the book idea? Does it reflect the personality of the person? A cohesive concept?”

Have any participants actually started writing their memoirs?

One example — Ellen Goldfinch is a writer (and retired librarian) who is writing her memoirs in the form of 70 letters. She calls it “the thank-you letters: an autobiography with tangents.” My hope is that designing a book cover might motivate others to start on theirs.

A lot of your artwork is political. Is this project political?

“Political” generally means “related to the dynamics of power in our society.” This project at its core says “Everyone has a story worth telling.” It then begs the question: Whose stories do we hear? Whose are unheard? And why? Who has the free time, resources and connections to write, publish, and disseminate a book about their life? Who doesn’t? In a way, “everything is political,” and this project is no different.